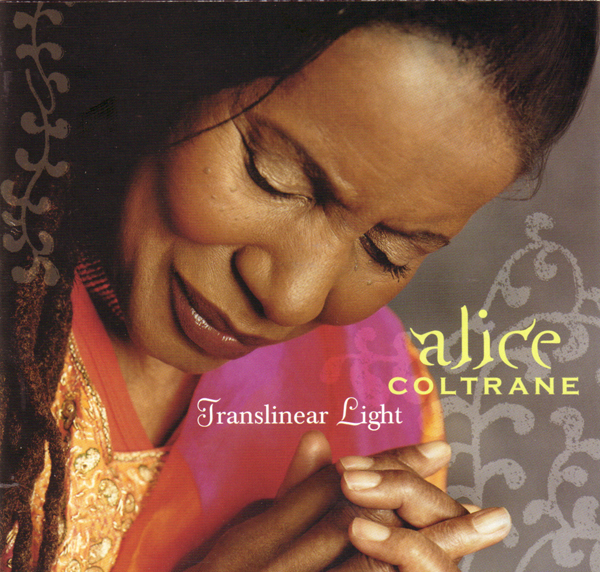

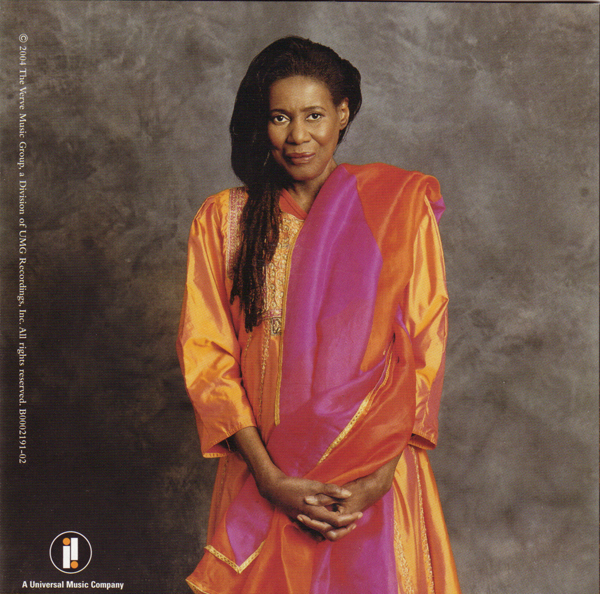

ALICE COLTRANE

1/ Sita Ram

2/ Walk With Me

3/ Translinear Light

4/ Jagadishwar

5/ This Train

6/ The Hymn

7/ Blue Nile

8/ Crescent

9/ Leo

10/ Triloka

11/ Satya Sai Isha

Produced by Ravi Coltrane

Alice Coltrane: Leader, Wurlitzer organ, Piano, Synthesizer; Ravi Coltrane (1,3,4,7,8,9): tenor saxophone, soprano saxophone,

Oran Coltrane (6): alto saxophone; Charlie Haden (3,5,8,10): bass; James Genus (2,4,7): bass; Jack

DeJohnette (1,3,5,8,9): drums; Jeff "Tain" Watts (2,4,7): drums.

2004 - Impulse! (USA), B000219102 (CD)

Thom Jurek (courtesy of the All Music Guide website)

Translinear Light is Alice Coltrane's first record for almost 25 years, during which time she has lived at her Vedantic Center ashram in California and released nothing outside some cassette-only devotional recordings. Already renowned before her retreat from the secular world for her Hindu beliefs, her albums had titles like "Universal Consciousness" or "Lord of All Lords", and wove Eastern-influenced playing, percussion and atmosphere into stunningly vast, soaring free-jazz compositions which preached simple messages of joy and praise. Journey in Satchidananda, which I tracked down after it was recommended by the hugely Coltrane-influenced Kieran "Four Tet" Hebden in a magazine article, sounds like a galactic battle between archangels and the asura (and possibly, as Terry Pratchett's CMOT Dibbler might have it, "a one thousand elephants!") being channeled through the frameworks of mythological tales with overwhelming force; it remains a record both uplifting and terrifying.

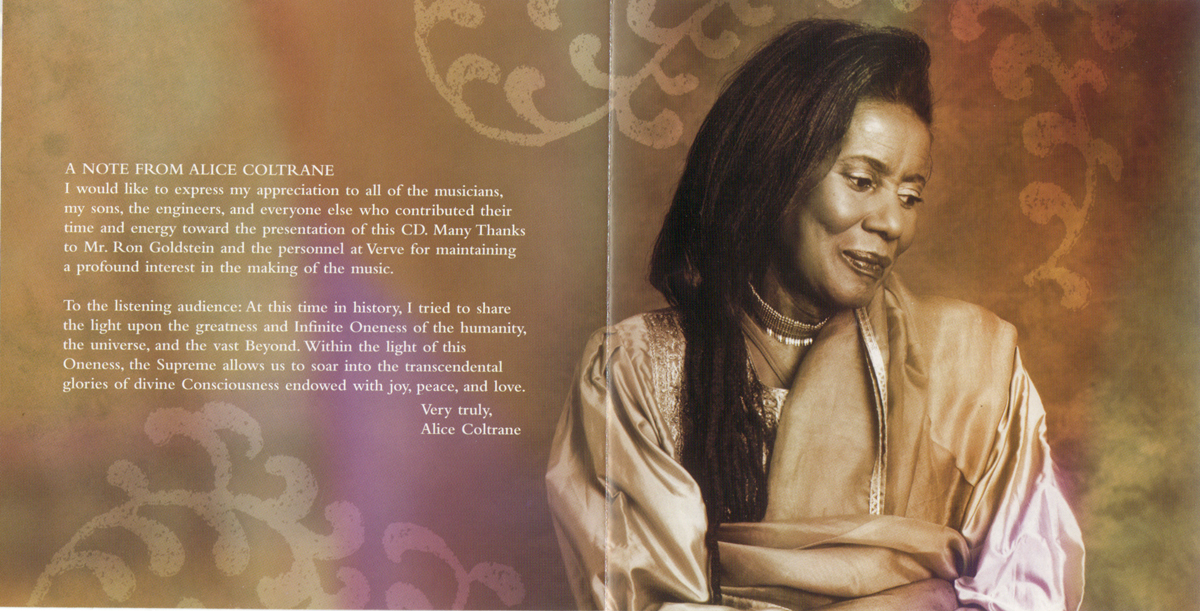

"At this time in history, I tried to share the light upon the greatness and Infinite Oneness of the humanity, the universe and the vast Beyond" goes a portion of Translinear Light's booklet dedication, but whilst the unabashed religious fervour is as plain as ever, the explosive drama of the music has ebbed, to be replaced by an unhurried calm of lambent depth, the group onslaught giving way to gently accompanied solos. The instrumental focus is on the leading lady's keyboard virtuosity (whether piano, synthesiser or her unique Wurlitzer organ sound) as set off by the tenor and alto saxophone playing of her two sons Oran and Ravi (the producer) and an understated frame of percussion and bass. Lyrical and assured, this is playing of simple gorgeousness that glides along with the free progression of improvisation whilst retaining the harmony and melodic grace of jazz standards. Indeed, the album opens with traditional Indian piece "Sita Ram", on which Coltrane's Wurlitzer sounds eerily like a sitar in places, and takes in reinterpretations of "Walk With Me" and "This Train" as well as two of her legendary late husband's compositions, "Crescent" and "Leo", before ending on the Wurlitzer-accompanied chanting of "Satya Sai Isha".

The mounting three-way delirium (and manic two-minute percussion solo) of "Leo" aside, Translinear Light is a peaceful example of the sensuality and individuality at the heart of jazz's emphasis on personal expression within group dynamics, and a searing reminder of how mesmerisingly beautiful sound can be: the tone of Ravi's tenor sax on "Jagadishwar" alone is enough to make me want to cry. While it is therefore a sad disappointment that Coltrane has chosen not to exercise her wonderful harp playing on this album (Joanna Newsom's success going some way to reassuring me that I'm not alone in mourning the quasi-disappearance of this instrument from the face of modern music), as a collection of luminescent music by someone both utterly at peace with herself and very obviously in love with life and her family this has both the glow and the finesse to enrapture. With any luck it will tempt a few more into the ranks of the faithful willing to exchange easy listening for something freer, more challenging and more deeply felt. Perhaps jazz (and life) is an answer in the form of a question, and perhaps not; either way there is much more to come, and jazz's legacy is very far from finished.

Stefan Braidwood (courtesy of PopMatters website)

At its best, music is a reflection of who we are, where we've been and where we're going. It transcends classification and, instead, becomes something personal, a powerful force that paints a clear and honest picture of the spirit of the performer. While some artists are concerned with the mechanics of music, the logic of how notes and rhythms fit together in new and intriguing ways—and there's absolutely nothing wrong with that—others view music as more of a conduit, a means of giving a certain physicality to the incorporeal.

Alice Coltrane, whose life has been inextricably tied with her departed husband John, removed herself from the conventional music scene over twenty years ago to devote her life to pursuits of a spiritual nature. While she hasn't stopped playing music in that time, she has felt it unnecessary and perhaps even a little counterproductive to continue participating in an industry that has become more about product and less about pure musicality. Fortunately, her son Ravi, an accomplished saxophonist in his own right, has managed to draw her out of her more transcendent pursuits to create Translinear Light, a richly rewarding album of music that has little to do with music as an exercise in technique and more as a means of conveying deeper expression.

That's not to say there isn't a great deal of skill behind this programme that consists of original music, both composed and improvised, as well as a number of traditional spiritual tunes and two pieces by John Coltrane, "Crescent" and "Leo." The supporting group of musicians includes bassists Charlie Haden and James Genus, drummers Jack DeJohnette and Jeff "Tain" Watts, and Ravi Coltrane on various percussion, tenor and soprano saxophones; Ravi's brother Oran makes an appearance on alto saxophone. The level of musicianship and empathy is uncommonly high.

Alice Coltrane has always had a distinctive piano style that combines rooted knowledge with more spirited flights of fancy. And her use of Wurlitzer organ is truly unique. On the traditional opener, "Sita Ram," for example, she manages to make the instrument's reedy texture sound more like a Tibetan oboe than a keyboard, making the notes bend and twist remarkably. On "Jagadishwar" and "The Hymn" Coltrane creates resonant synthesizer washes that suit the tranquil ambience of both pieces.

Other pieces are, if not more conventional, more in synch with what some might expect from a jazz record. Her readings of "Blue Nile" and "Crescent" sound as if she has drawn a direct line back to the mid-'60s work of husband John. "Leo," where she again uses the Wurlitzer to create a surprising sonority, links more directly to the more outer-reaching free excursions near the end of John Coltrane's life, when Alice was an integral part of the group.

With Translinear Light Coltrane has created a work that honestly and unassumingly demonstrates the healing power of music, bypassing more intellectual concerns and instead going straight for the heart of the matter.

John Kelman (courtesy of the All About Jazz website)