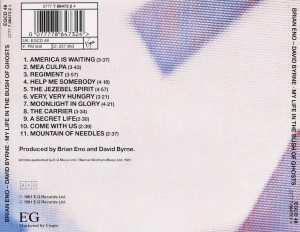

BRIAN ENO/DAVID BYRNE

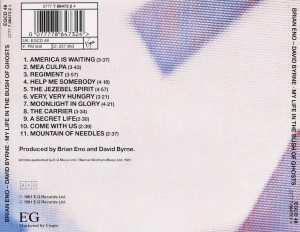

1/ America Is Waiting (Eno,Byrne) 3.36

2/ Mea Culpa (Eno,Byrne) 3.35

3/ Regiment (Eno,Byrne,Jones) 3.56

4/ Help Me Somebody (Eno,Byrne) 4.18

5/ The Jezebel Spirit (Eno,Byrne) 4.55

6/ Qu'ran (Eno,Byrne) 3.48

7/ Moonlight In Glory (Eno,Byrne) 4.19

8/ The Carrier (Eno,Byrne) 3.30

9/ A Secret Life (Eno,Byrne) 2.30

10/ Come With Us (Eno,Byrne) 2.38

11/ Mountain of Needles (Eno,Byrne) 2.35

12/ Pitch to Voltage (Eno,Byrne) 2.38

13/ Two Against Three (Eno Byrne) 1.55

14/ Vocal Outtakes (Eno Byrne) 0.36

15/ New Feet (Eno Byrne) 2.26

16/ Defiant (Eno Byrne) 3.41

17/ Number 8 Mix (Eno Byrne) 3.30

18/ Solo Guitar with Tin Foil (Eno Byrne) 3.00

Recorded at RPM, Blue Rock, Sigma, New York, Eldorado, Los Angeles and

Different Fur, San Fransisco, August 1979 to October 1980

Engineer at RMP: Neal Teeman

Assistant: Hugh Dwyer

Engineer at Blue Rock: Eddie Korvin

Assistant: Michael Ewasko

Engineer at Eldorado: Dave Jerden

Assistant: Georg Sloan

Engineer at Different Fur: Stacy Baird

Assistants: Don Mack and Howard Johnston

Engineer at Sigma: John Potoker

Produced by Brain Eno and David Byrne

Mastered by Greg Calbi at Sterling Sound

John Cooksey (4,6,16): drums; Chris Frantz (3): drums; Dennis Keeley (2): bodhran;

Mingo Lewis (5,8): bata, sticks; Prarie Prince (5,8): can, bass drum; Jose Rossy (7):

congas, agong-gong; Steve Scales (4): congas, metals; David van Tieghem (1,3):

drums, percussion; Busta Jones (3): bass; Bill Laswell (1) : bass; Tim Wright (1) :

click bass; VOICES - (1) Unidentified indignant radio show host, San Fransisco, April

1980; (2) Inflamed caller and smooth politician replying, both unidentified. Radio call-

in show, New York, July 1979; (3) Dunya Yusin, Lebanese mountain singer; (4)

Reverend Paul Morton, broadcast sermon, New Orleans, June 1980; (5) Unidentified

exorcist, New York, September 1980; (6) Algerian Muslims chanting Qu’ran; (7) The

Moving Star Hall Singers, Sea Islands, Georgia; (8) Dunya Yusin; (9) Samira Tewfik,

Egyptian popular singer; (10) Unidentified radio evangelist, San Fransisco, April 1980.

Track 1 arranged by Eno, Byrne, Laswell, Wright and van Tieghem

Track 3 arranged by Eno, Byrne and Jones

1981 - Editions EG (UK), EGLP 48 (Vinyl)

1981 - Polydor (France), EG 176 2302100-1 (Vinyl)

1981 - Sire Records (USA), SRK 6093 (Vinyl)

1989 - Editions EG (UK), EGCD 48 (CD)

1999 - EMI (USA), 86473 (CD)

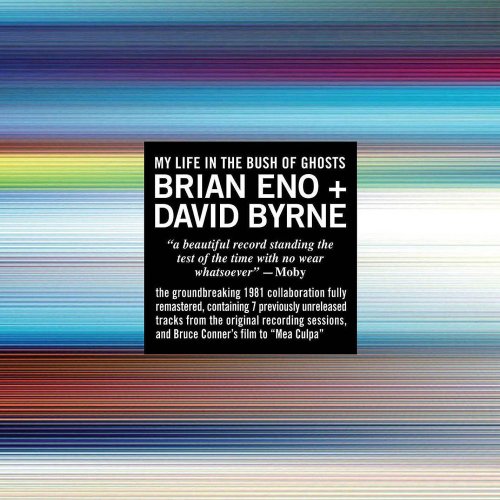

2006 - Nonesuch (USA), 79894 (CD)

Note: Tracks 12-18 only appear on the 2006 reissue.

What's the difference between using evangelists' rhetoric as lyrics (for "Once in a Lifetime" on Talking Heads Remain in Light) and using the voice of New Orleans preacher Reverend Paul Morton in "Help Me Somebody"? Plenty. "Once in a Lifetime" is obviously Byrne's creation, complete on its own terms. "Help Me Somebody" is a falsified ritual, with its development truncated and its rhythm deformed. A pseudodocument, it teases us by being "real." Even more annoying is "The Jezebel Spirit," which utilizes a recorded exorcism. Byrne and Eno latch onto the rhythm of the exorcists dry laugh for the backup, but the fade out before we find out what happened to the possessed woman - which would have been a lot more interesting than the chattery band track. Blasphemy is beside the point: Byrne and Eno have trivialized the event.

Still, electronic music does have an honorable tradition of messing with speech sounds. "America Is Waiting," "Mea Culpa" and "Come with Us" - rhythmic nuggets from an editorial, a talk show and yet another evangelist - are smart, funny-creepy transformations, justifiable because they don't promise a narrative payoff. But messing with music is a more dubious proposition. You'd think if Algerian Muslims had wanted accompaniment while they chanted the Koran ("Quran"), they'd have invented some. Or if Lebanese singer Dunya Yusin craved a backbeat, she could have found one (Byrne and Eno's "Regiment" sounds like something from the Midnight Express soundtrack).

When they don't succumb to exoticism or cuteness - luckily, that's most of the album - the Byrne-Eno backups are fascinating, complementing the sources without absorbing them. David Byrne and Brian Eno pile up riffs and cross-rhythms to build drama, yet they keep the cuts uncluttered and mysterious. As sheer sound (ignoring content and context) many of the selections are heady and memorable. My Life in the Bush of Ghosts does make me wonder, though, how Byrne and Eno would react if Dunya Yusin spliced together a little of "Animals" and a bit of "The Paw Paw Negro Blowtorch," then added her idea of a suitable backup. Does this global village have two-way traffic?

A review by Jon Pareles, from Rolling Stone, 8/2/81 (courtesy of the typing skills of Steve, posted on the Hyperreal website)

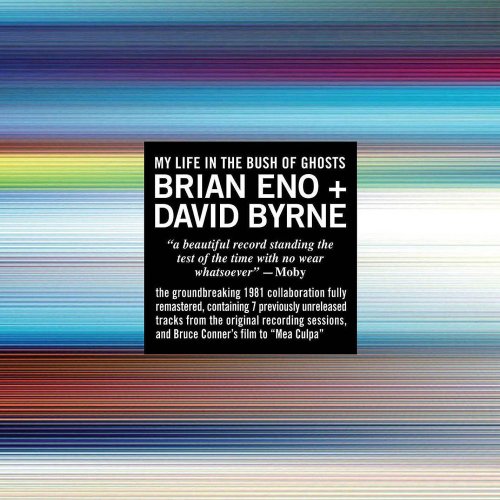

As David Byrne describes in his liner notes, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts placed its bets on serendipity: "It is assumed that I write lyrics (and the accompanying music) for songs because I have something I need to 'express.'," he writes. "I find that more often, on the contrary, it is the music and the lyric that trigger the emotion within me rather than the other way around." Maybe because it's so obviously the product of trial-and-error experimentation, Bush of Ghosts sounded like a quirky side project on its release in 1981; heck, it didn't even have any "songs." But today, Nonesuch has repackaged it as a near-masterpiece, a milestone of sampled music, and a peace summit in the continual West-meets-rest struggle. So we're supposed to see Bush of Ghosts as a tick on the timeline of important transgressive records.

It mostly holds up to that scrutiny. An album that's built on serendipity-- on Brian Eno fooling around with a new type of drum machine, on syncing the hook in a tape loop to a chorus, on finding the right horrors on the radio-- can't score 100%. But even if you cut it some slack, crucial parts of the album don't sound as intriguing today as they once did-- namely, all of the voices.

The sampled speech from various, mainly religious, sources ties the album into a long and prestigious history of artists who used found sound, which David Toop capably outlines in the liner notes. It's still the secret sauce that provokes a reaction from the listener. But what reaction you have lies outside of Byrne's, Eno's, or your control. On the first half, where the voices are least chopped up, it's difficult to divorce them from their origins. A couple of tracks read as satire-- "America Is Waiting" sounds like Negativland with a way better rhythm section-- and others as kitsch. "Help Me Somebody" pulls a neat trick by turning a preacher into an r&b; singer, but the exorcist on "The Jezebel Spirit" doesn't raise as many hairs on the back of my neck now that taping a crazy evangelist has become the art music equivalent of broadcasting crank phone calls. We can't just hear them for their sound or cadences without digging into the meanings, and not everyone will find the meanings profound.

On the other hand, the rhythm tracks still kick ass 10 ways to Sunday, thanks both to the fly-by apperances of Bill Laswell, Chris Frantz, Prairie Prince, and a half dozen others, and to the inspired messing about of Eno and Byrne as they turned boxes and food tins into percussion. Tape loops are funkier than laptops, and the modern ear is so aware of the digital "noodging" of a sample to a beat that the refreshingly knocked-together arrangements of Bush of Ghosts are a vast improvement. At one stage of the project, they dreamed about documenting the music of a fake foreign culture. They largely pulled it off, and you can tell a lot about this far-off place from its music: It's a futuristic yet tribal town made of resonant sheets of metal and amplified plastic containers, that the populace has to bang constantly in perfect time to make the traffic move, and the stoves heat up, and the lights flicker on at night, and to coax mismatched couples into making love and breeding new percussionists.

The seven bonus tracks will provoke more arguments than they settle. The setlist of Bush of Ghosts has changed several times over the years, and the diehard fans will still have to swap left-out cuts that aren't resurrected here; most famously, "Qu'ran", an apparently sacreligious recording of Koran verses set to music, doesn't get anywhere near this reissue. The songs that are here include a few that sound almost finished, including "Pitch to Voltage", and others that would fit almost as well as anything in the second half of the disc. The last cut, "Solo Guitar with Tin Foil", features someone, presumably Byrne, playing a haunting tune on a guitar with an impossibly clean tone-- a fitting end to an album that, for all its transcontinental fingerprints, sounds strikingly free of impurities.

Though Bush of Ghosts was a link in the chain between Steve Reich and the Bomb Squad, I'm not convinced that this talking point helps us enjoy the album. However, Nonesuch made an interesting move that could help Bush of Ghosts make history all over again: they launched a "remix" website, at www.bush-of-ghosts.com, where any of us can download multitracked versions of two songs, load them up in the editor of our choice, and under a Creative Commons license, do whatever we want with them.

As I write this, the site hasn't launched, and even if it were up, I can't tell how lively its community will be, how edgy the remixers can get, and how many rules will pen them in. Nonesuch copped out by posting only part of the album, instead of every piece of tape they owned, and I suspect that the bush-of-ghosts.com site may just be a corporate sandbox for wannabe remixers. But I could be wrong; I haven't tried to submit my mash-up of "Qu'ran" and Denmark's National Anthem yet. What matters is that they started the site and released these tracks, and by doing so, they put a stake in the ground-- not the first one, but an important one-- for Creative Commons licensing, Web 2.0 album releases ("this is an album where you participate!"), and the culture of remixing.

And by handing over their multitracks, Byrne and Eno also make a powerful acknowledgement of their own helplessness. It is a basic but real fact of our time that sampling can work both ways. In the 80s, you could fairly make an argument that Byrne and Eno were the Western white men appropriating all kinds of Others, be they domestic and primitive, or foreign and exotic. Now the world can return the favor: Anyone can rip this work apart and use it any way they please, and you can bet that if some kid in the Third World sends a killer remix to the right blogger, it'll travel faster and farther than this carefully curated reissue. Byrne and Eno counted on a certain amount of serendipity in their studio; today, they can witness the serendipity of what happens to their killer rhythm tracks-- the ones they released, and all the others that people will use anyway. And the strongest message they could send is not only that they've relinquished control, but that they admit they already lost it-- whether they like it or not.

8/10

Chris Dahlen (courtesy of the Pitchfork website)

I first encountered My Life in the Bush of Ghosts almost by accident, seeing it mentioned in passing somewhere in relation to the Talking Heads’ 1980 masterpiece Remain in Light. After I tracked down a copy I took the odd album to heart, listening to it repeatedly in an attempt to understand in just what ways this strange missing link had influenced the music that had come after. Then as now, the album remains strangely compelling if slightly bloodless, a fascinating conceptual leap into unknown territory that loses little importance for its status as an essentially inchoate entity. The recent Nonesuch reissue presents the album in as pristine a context as possible, allowing the listener to see the album in as close to the original spirit as the artists intended.

Whereas oftentimes My Life in the Bush of Ghosts has been described as “influential”, I think a better term would be prescient. Influence is an extremely tricky field to measure. There is no way to know just how many people heard the album and were directly inspired. It is easier to say merely that the album was amazingly accurate in its predictions. Whether or not it helped precipitate the subsequent movements (hip-hop, world and electronic music) for which it served as a vanguard, it was ultimately less a catalyst than an anachronism, an album out of time, the kind of artifact that becomes increasingly important in hindsight, long after its initial outlandish predictions have been vindicated by time and circumstances. Whereas it might have seemed odd in 1981, now it is accepted in even the most conservative quarters that sampling is ubiquitous; world music has entered the global pop marketplace and become more than simply an ethnographic concern, and the role of the musician has changed to reflect these technological and sociological realities.

On the face of it, it’s hard to accept Byrne and Eno as anything more than bystanders in the origins of modern music. Certainly, it would be hard to deny the importance of either the Talking Heads or Eno’s work with Roxy Music, David Bowie, or his own long solo career, but I think that My Life in the Bush of Ghosts captures an interesting moment in both mens’ careers, where they sat on the precipice between being active participants in the evolution of pop music and mere observers. The word Byrne and Eno use to describe their conception of the new paradigm is revealing: curator. There is something hopelessly passive in the term. Curators work in museums, preserving art and history so it can be passed down, in stasis, through to untold future generations. By definition they cannot be active participants. Would Orbital or DJ Premiere or Moby or Danger Mouse define themselves as curators? It’s an odd choice of words that reveals as much about Byrne and Eno’s preoccupations as about the music itself.

Because, let’s be honest: world music existed just fine before a bunch of upper-middle-class white record buyers decided to start paying attention to Fela Kuti and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Hip-hop was already beginning to bubble up from its regional origins before Byrne and Eno ever decided to play with samples. Although it probably didn’t seem like it at the time, Byrne and Eno were working against the prevailing cultural forces by seeking to capture the spirit of an ongoing evolution in a static medium. Artistic revolutions are created by bold, unselfconscious applications of will and exuberance, and in this regard Byrne and Eno were little more than lightning rods, attracting a heady charge from the contentious atmosphere that permeated their surroundings.

In this regard, it’s hard not to see Byrne and Eno as akin, in spirit if not in practice, to the same folk music curators who decried the influence of folks like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie on the art form of American folk music. By introducing popular recorded versions of regional standards, Seeger and Guthrie placed their own artistic stamp on what had been an ongoing and generational medium, essentially locking what had been a constantly evolving art into set forms that would be recognized in perpetuity. But even if Byrne and Eno were essentially correct about the pliability and plasticity of future musical forms—an amazing fact considering that there is no way they could have accurately predicted the invention of the sampler, let alone scratching, Cubase, or Pro-Tools—they were dead-wrong in predicting the demise, or even a weakening, of the link between author and performer. Just because music is plastic doesn’t mean that the economic and social systems under which music is disseminated is particularly pliable. They encountered this in trying to clear the samples that ensured My Life in the Bush of Ghosts stayed on the shelf for almost two years following the completion of recording. The permanence of recorded music means that the “causal link between the author and the performer” will never be eroded. Rather than contributing to an erosion between these distinctions, the digital age has ensured that every recording, from a full symphony to a three-second sample of an obscure funk bassline, can be tracked and litigated. Probably not the “brave new world” Byrne and Eno anticipated.

Listening to My Life in the Bush of Ghosts all these years after its original release, and many years still since I first discovered it, it sounds surprisingly contemporary. What was once inconceivably avant-garde has become dreadfully familiar. Sampling spoken dialect—as with the radio hosts on “America is Waiting”—is almost rote. The African polyrhythms that once seemed so exotic have been, more or less, assimilated into the language of pop music, such that it’s possible to draw a line between the violent funk of “Mea Culpa” and many branches of modern house. By means of comparison, there are in fact very few rhythmical possibilities that have gone unexplored either by contemporary hip-hop and R&B or avant-garde IDM. Any number of these tracks wouldn’t have sounded unusual on an early Autechre LP, or even cut, looped and placed under a Missy Elliot rap.

So where does that leave us? Coming to terms with an artifact like My Life in the Bush of Ghosts is as difficult as reading the future. It’s still possible to be bewitched by the album, if the listener can overcome the waves of self-congratulatory seriousness. It deserves a place in your collection, if less for any enduring importance than an abiding interest that serves as a testament, above and beyond any discussion of the album’s provenance, to Byrne and Eno’s sure-footed musical instincts. It sure sounds prescient, but at the same time there’s something almost painfully naive about it, like seeing the futuristic predictions made by people living decades in the past. Sometimes the general shape of things to come can be predicted with certainty, but it rarely comes to pass with the optimism our ancestors summoned.

7/10

Tim O'Neil (courtesy of the Pop Matters website)