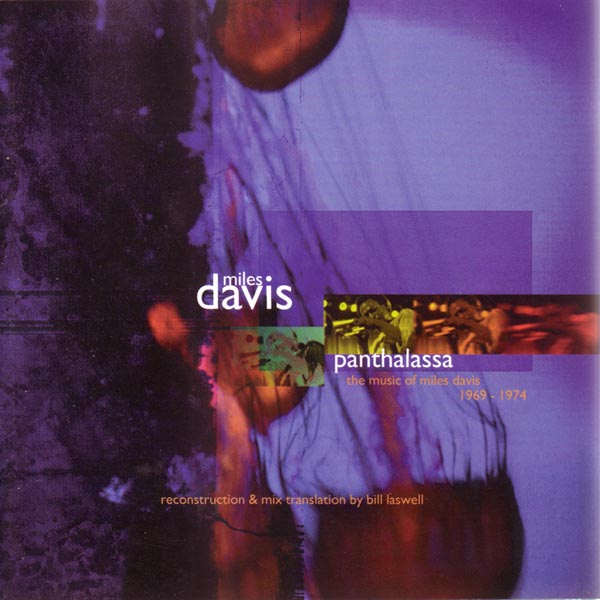

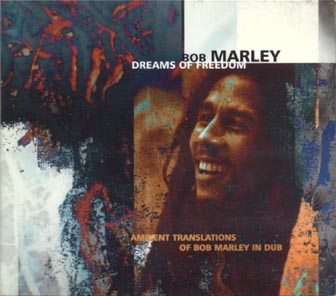

GHOSTS IN THE MACHINE

A musical renaissance man for the millenium,Bill Laswell's ambient remixes of Bob Marley and Miles Davis

have added a new dimension to their music and the art of remix. He talks to Kevin Martin

KM: How did the Bob Marley and Miles Davis remixes come about?

BL: The Marley project was the result of a conversation with Chris Blackwell ([former] head of Island Records) in Jamaica. We had worked together on a record called Lost In the Translation, which had combined and reconstructed a lot of pieces previously released on my Axiom label. He mentioned it might be interesting to use the same approach with Marley's music. It took a long time to secure the tapes, whilst investing even more time in deciding how to approach things and getting a feel for the whole experience. There was more time spent thinking about the project than actual time spent experimenting in the studio.

The Miles project came about knowing that Sony would be re-releasing back catalog. The idea was that something reconfigured, reconstructed, or even previously unheard would be of great value.

KM: How did you select the Marley songs to be remixed?

BL: I listened to his whole catalog, everything that was available. Then I thought about it at length and also had time to read a great deal about Marley's time in Jamaica, his evolution as a musician and later as an icon. I took a lot of that into perspective, paying attention to how much respect he had all over the World.

KM: So you were trying to trace a musical narrative - a sonic bibliography - with the record?

BL: Yeah, I wanted to bring out the spirit that led to such respect. Because of his strength of will, it becomes almost religious in the way his followers are so devoted, it's beyond right or wrong. It was a very different approach to the Miles though. But I think all of it is like writing or film making because you get a much bigger picture than just sonic. Itís much more than just experimenting with sound.

KM: The pieces seem more devotional, almost hymn-like. Was that the aim?

BL: Yeah, that was a totally conscious desire.

KM: Did you approach it in that manner because you were worried about people's possibly adverse responses to the mixes?

BL: No, I approached it that way because I invested into the history of it and the value of the artist. If Bob Marley had been an avant garde composer the world wouldn't have recognized his name. In fact he was dealing in pop culture with a more accessible sensibility and I thought it would be a little stupid to betray that. It was an attempt to bring out the spirituality which is already inherent in each piece as an atmosphere or environmental tone.

KM: Do you feel there were definite parallels in the lives of Marley and Miles?

BL: Yeah, but I knew Miles personally and had a lot of conversations with him about the records which I've ended up remixing, whereas I didn't know Marley. I spoke to Miles about a lot of things - about working on future music which I think would of had a lot more in common with the music we've just mixed than the music he did in the '80s. He was also convinced that he had made a breakthrough with On the Corner. He knew that record was a departure from how people were putting music together and was ultimately disappointed with the response from critics at the time and the total lack of commercial success. He felt he had created a new style, which in fact he had.

KM: Do you think he was keen to take total credit for advances away from his producer of that time, Teo Macero?

BL: Well I don't think in certain cases that alot of credit should be given to Teo Macero. He was a salaryman; he did not work for Miles, he worked

for Columbia, and there's a lot of stories that make that a truth. With In a Silent Way, the main theme that the group was working on was a

30-minute piece which didn't even get on the final record. What you hear on the record is them playing around the theme. There's a lot of music and

a lot of brutal editing. You'll hear the same piece of tape twice on two different pieces. The only excuse for that is the label saying "hurry up

and put the record out".

BL: Well I don't think in certain cases that alot of credit should be given to Teo Macero. He was a salaryman; he did not work for Miles, he worked

for Columbia, and there's a lot of stories that make that a truth. With In a Silent Way, the main theme that the group was working on was a

30-minute piece which didn't even get on the final record. What you hear on the record is them playing around the theme. There's a lot of music and

a lot of brutal editing. You'll hear the same piece of tape twice on two different pieces. The only excuse for that is the label saying "hurry up

and put the record out".

KM: When you approached the songs you chose, was it because you felt that you could enhance something that wasn't there? Or was it because you felt there was something lacking in the original sound?

BL: For Marley it was to bring out the spirit of the thing and to enhance the low end or basslines and then to treat it with ambient atmospheres. Whereas with Miles it was based on the reality that although these records were fairly well recorded for the time, you're using certain instruments that were mixed like jazz records. If you listen to the original recording of 'Rated X' from Get Up With It, it just sounds horrendous, it's like somebody did a bad rough mix as a demo.

KM: Were there particular tracks by Miles which converted you to this approach?

BL: It wasn't so much a single track as an album. I always thought when those records were released that the album is what you get at the store, while the experience that made the recording is spread over 50 multi-track tapes, so you're getting an edited cut-up - a mere fraction. You're not really getting the experience of what really happened with that music or those musicians.

When On the Corner first came out, I can remember all those two-star reviews with people saying how terrible it was, yet for me it was the same feelings as when hip hop first got abstract - going against pitch, against the rhythms. On the Corner represents that type of freedom to me. That was the beginning of an emergent form of hip hop, and I connected to it immediately. On the Corner is really just two basslines over a beat, and all just cut up. You hear those little things which are just two minutes long; they're just quick cuts pulled from the longer 15-20 minute beats. I have six reels of outtakes from On the Corner which didn't even make the record.

KM: With the Marley project, was it the music or the spirituality behind it which made the initial impact?

BL: I think there was something believable about what he was saying and the conviction translation was even more unknown, as regards to where he was coming from and what it meant. Also the rhythm section was really interesting and strong in it's own way too; it had a kind of mysterious character that also appealed. Working with the tapes where you can just isolate individual bass and drum takes you really here it differently cause the bass is playing with the band but sometimes not even that close to what, let's say the hi-hat is doing in the song, but he's still making the music work, giving the bass another function with a lot of melody.

KM: How do you feel about criticism that remixing is a destructive act, centered around the remixer's ego?

BL: I think there's a lot of destructiveness and a lot of unlicensed experimenting with music. People think that just because they've made a couple of records that they're an authority on reconstruction. I think music's a much deeper experience which comes completely out of the unknown. There should be a little more value given to that. That's not to say that you have to treat Bob Marley or Miles Davis like some sacred music, which it is, but it's all ultimately sound. There is a history to it, however, and I do have a memory of being affected by it and it affecting the decisions I made when mixing it. If remixing is raw, experimental and fun, that's great, but I almost never hear it approached as composition. Because to me, everything on tape is potential composition, which to me means the person approaching it should be a composer. I think you can evolve with that much more but I don't think anyone's really started. It's easy to get a sampler and some fx and make noise and put stuff out. Sometimes it can be incredible but a lot of times it's done by people who'd be more suited working at record companies.

KM: Was there a confrontational appeal, remixing music knowing it would annoy reggae or jazz purists?

BL: In the case of the Miles period I picked, the music was originally turned inside out and well tampered with - there was nothing pure about it. What we got was endless tape, condensed and edited.

KM: Is there any music which you felt shouldn't be remixed?

BL: It's hard to say because a mix is a smaller tape made from a bigger one. And what you're calling the mix is the result of that specific day's work and it really gets down to what happens in the air during the performance. But then what really happened from what perspective? Where were you standing? You don't even have to do it with tape. You can be at one end of the a room and experience something completely different. You're hearing it like a microphone hears it, but if you have several microphones, you'll hear it different anyway. When that gets transferred to a smaller tape, we call it a mix but the consumer calls it a finished record. All they're really talking about is a version. Editing is what determines the sound of a lot of the music we're talking about, especially in the case of Miles Davis. Listening to In a Silent Way masters, you wouldn't believe what was done to reach the end result.

KM: When you approach remixing, is it a means of saying a song needn't be finite? Is it about keeping a song alive?

BL: In a way there's no remixing; it's mixing, period. And you can mix indefinitely. If people stay too close to the original they're more obsessed with the photograph than with the thing that's being photographed. I mean, how many pictures do you want of an object before you think you've seen enough of it? That's how many times you want to remix it.

KM: So you think there's a logical end to a mix?

BL: With the work I did, I call it the end for me, but then someone else could do something completely different. I wouldn't go back myself and do a re-whatever on those records because it was a very devotional, exhaustive experience.

KM: A lot of people criticize the popularity of remix culture as indicative proof of the lack of innovative new music around. Do you agree with that?

BL: Well there's always a lot going on and there's persistent advancements, with people using new technology to remanipulate endlessly. Some of it's

interesting and some of it is major breakthrough material. But unfortunately the major realization is that there's less and less of a certain kind of

committed person, and now that someone like Tony Williams is no longer with us, there's not going to be anyone quite like that again.

BL: Well there's always a lot going on and there's persistent advancements, with people using new technology to remanipulate endlessly. Some of it's

interesting and some of it is major breakthrough material. But unfortunately the major realization is that there's less and less of a certain kind of

committed person, and now that someone like Tony Williams is no longer with us, there's not going to be anyone quite like that again.

KM: Are you saying that music made now will be more about a relationship to changing technology as opposed to social interaction?

BL: Exactly, and it's all affordable. You can do something relevant now with the right list of gear. Before, musicians had to invest and sacrifice. But you must remember that is the sound of someone getting older talking. That's what happens.

KM: The other criticism of remix culture is that labels will be more interested in short-term low expense remix investments than long term new group investment. Do you think that's true?

BL: In most cases, yes. Making money has become it's own star system. Making money eclipses everything. Good or interesting is no longer important. Soundtracks, for example, are now totally about making money; no more scores. Unless it's based in Tibet, when even the company realized you can't license the Smashing Pumpkins for the background. They think developing new acts would sabotage their cash flow. Jazz is the worst. It should have been destroyed years ago; that whole Marsalis sensibility is still ruling jazz.

KM: Is a dub mix as relevant as the original?

BL: I would say for me it's probably more relevant. I used to go out and buy dub records, finding vocal-less mixes or even looking for those that had no horns either. The more minimal the better.

KM: How do you feel about people remixing you?

BL: Fine. With the Oscillations record I wouldn't even have known that the sources came from the same recording and I think that's very good. It makes a whole new records and even gave me ideas about approaching new material.

KM: Is drum and bass the next major musical evolution?

BL: I don't think so. I think it's the next evolution of the rhythm section. But I think you could hear that sound 20 years ago if you listened to an old dub record where someone sped up a double time delay against a half time beat. A lot of Jamaican producers reckoned to have instigated jungle. I liked it then and I like it now. There are drummers who are thinking about the technological sense of dislocation of drum and bass but are not physically able to do it. I know Jack DeJohnette is listening to that music and is thinking about how to incorporate it. Heís not intimidated by it because he loves it.

In fact I've just done a record with Zakir Hussain for Axiom, where a lot of the conflicting tempos are like jungle. But he's playing the loops and he's a tabla player. It's kinda scary, seeing what he can do minus a kit and then reacting by saying, "Oh, is that it," when he's finished. He's probably the most highly evolved rhythm player there is. And that was the concept; to show a human in that position rhythmically.