JAH WOBBLE INTERVIEWS BILL LASWELL

New York, early 1999, broadcast April 1st, 1999 on BBC Greater London Radio

Jah Wobble: How did you get started?

Bill Laswell: I started really young.... 12, 13. I started getting interested in playing instruments, mostly because people around me were doing it. There wasn't specifically a style of music, although at the time it was rhythm & blues mostly. It wasn't like a lot of rock stuff, it was mostly people trying to play rhythm music. And everyone seemed to play drums or guitar, and there weren't a lot of people playing bass, so whoever could play those instruments would make groups and have activities. There weren't any people playing bass, so I would take a guitar and take 2 strings off and use that as a bass. And then gradually I realized that by having that I would probably get involved in more situations because nobody was doing it, everybody wanted to play drums or guitar - that's how it happened to be the bass, it wasn't like an obsession toward that instrument at the time. But then once I got into it, and I saw the function of it in that kind of music I became more and more interested in developing a kind of a feel or way of playing with drummers that was special, whereas I could hear people that weren't quite doing that right - it was pretty obvious when it wasn't working, and it was obvious when it was. And I wanted to figure out a way to listen so you'd push & pull with time, no matter how simple it is, but you get into that from the beginning, that sort of subtle science of how you build a line, a repetitive line.

JW: What were your influences at the time?

BL: Probably James Brown and stuff where the lines would stay the same in a piece - not so much rock, it was just lines starting, lines and beats. Which is no different now than what you do if you are interested in creating hip hop or dub-related stuff, it's the same principle that would go into making minimal repetitive music now. So everything else gradually happened later from that rock music and then hearing jazz people, and then one thing gradually leads to the next. From hearing jazz records I started to hear music from other cultures, like from hearing Coltrane or Pharoah or Miles Davis you'd hear tabla and African influences and Eastern influences and you started moving towards that stuff.

JW: What is the influence of repetition and loops in your music?

JW: What is the influence of repetition and loops in your music?

BL: You have to work with people who could relate to that - a lot of people were into that, so I would just be playing a bass line, people are playing beats and other things you would play with the drummer. There's no need to put 5 things in the same frequency together or things that are playing a similar phrase, so you begin to learn to decorate things so that they don't cancel each other out, which happens in all kinds of music. So you have highs and lows and mid-range and you look at it first as sound on a tone scale and then the next thing is the harmonic side of it: what works and what doesn't, which has always been trial and error and fairly intuitive - the same as the tone idea. And that applies even now to whatever it is I'm doing, it's always finding things you can fit into a picture where something doesn't cancel the other part out, because it's in a similar area. Everybody has a different way of doing that, and I think it can be really advanced without that much technical information if it's really an intuitive perception - you can do it totally improvising. But it then creates something that's very thought-out and very constructed, just based on a repertoire of experience, like how to quickly put things together. Sound though - that's in the same way that people use noise as composition - I see it like sound. It doesn't necessarily has to be a perfect configuration of chords thought out in a sequence that repeats itself exactly at the same moment every time it comes around but you create just a flow.

JW: How about texture and tonality in music - particularly composers such as Stockhausen?

BL: I was always impressed with just the sonic quality and the flow of Stockhausen's work, but it's more the music that deals with electronic sounds and not so much the vocal music from later on - more I guess from the 60s period, but yeah that was impressive. But I'm influenced by so many things - everybody is I think.

JW: What about Miles?

BL: The period for me that's interesting of Miles is the electric period and it's exactly `69 until the time that he retired which was around `75 . And the period up to that point I'm sure he was a great innovator in jazz, which I've never had much interest in - I didn't grow up with jazz, I grew up with that music. When I first really seriously started listening to him it was at the time that music was happening . And from the time before, well, sure it was a great thing for jazz and he was a great artist, but something happened around `69 that was very interesting to me. What he did, because he was in a position to of course, because he was a name in jazz, what he did was opened the door that nobody really recognized as an opening. They just thought well, here's a guy trying to sell more records because Clive Davis told him to go rock or something, or to look different and sound different and emulate Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix and we'll make more money, but it wasn't just that - that was certainly in there, but there was a lot more to it, in that he was really interested in moving out of where he was, with no respect for genres, for styles, for what jazz is supposed to represent. And what he did with records at that time I think was make an opening and people just didn't recognize the opportunities that were being presented by that, because their head was not ...they weren't able to experience something immediately like that and just jump into it and do it, because they're too conditioned from their own academic learning, their standard, their ways - what they're supposed to respect, what they're not supposed to do in order to stay within a certain framework of "jazz". So critics especially, and musicians, didn't support that, and the small following of people who did - it wasn't that many at the time - it was considered a failure I think, but it was a major breakthrough that hasn't completely broken through yet.

I was very inspired to hear the later work of John Coltrane, which would have been `65-`67, and that's going pretty far back. And in the same case I knew he was a great innovator and a great saxophonist and even a valuable thinker, but I wasn't interested in the genre he was in before `64-`65 which was very much in the tradition of jazz, but at one point he broke from that as well, in an even more extreme way that Miles - it was a different way. It wasn't using repetition, but it certainly broke the mold, it broke out of the prison that everyone was put in of notes & chords and rhythm.

But I don't think you can get beyond, I don't think you can get that far into anything by emulating someone else. I think without having your own voice and your own contribution I don't see how you can do anything but continuously xerox that contribution or shadow it in a way. But I think there are a lot of players that have their own voices & their own things to say - unfortunately because it's original you won't hear about them, because you'll only really hear about people that are emulating the people from the past, and that's what they call the "tradition", preserving the tradition of the great American art form, which is jazz. It's emulating and carrying on that tradition, which to me only means reproduction of something that's happened before. So I think there are people in composition, I think Henry Threadgill is writing interesting things, I think even Steve Coleman sometimes is trying different things. His writing is influenced by other things, but it's also a collage because it's bringing in elements from other cultures and styles that aren't strictly in the jazz tradition. Graham Haynes is a cornet player - he has a sound and a style that you wouldn't say is emulating Miles, you would say it reminds me of Miles in spirit but you might relate it more to Olu Dara who had his own sound - and because he did and wasn't aggressive as a performer and entertainer, he's not a name everyone knows, but his statement is valid musically, you just can't exploit it. Because he's not trying to be exploited.

JW: Why did you start your own label?

BL: Well I always wanted to do that and I tried with different companies to do it because I just felt that to continuously go around trying to sell ideas to companies one by one was very time consuming and not always that enlightening - the kind of response you get from people. So Axiom started around `89-`90 at a time when Chris Blackwell had just sold Island to Polygram, which meant that there was going to be a transition in the things that he was doing and it looked like a good time to approach someone about a label. He seemed the obvious choice I thought, because it seemed that there weren't that many people were interested, even in the music industry that listen to music, outside of just money-orientated things, so I thought that was a good time and it was an opportunity to try to make some records that I felt in a lot of cases would help a lot of musicians. But it was also a way to do something that wouldn't have happened otherwise. It was just ideas, so we managed over a period of a few years to create about 30 records which I'm sure most of them wouldn't have happened, 90% of them wouldn't have happened if it hadn't have been for that situation.

JW: How do you see the future with regard to CD formats?

BL: People say that eventually you can download everything, sell your own things directly, but I do see CDs being around for some time, because it's like - why are we still using gasoline or why are we paying for electricity? It's going to be there because there are these huge businesses and corporations that exist and they're not going to go away overnight. People will still make CDs I think. I think DVD will be successful because of the format - because it's a format that's quite popular. There's so much money, there's just billions of dollars, so with a little tightening up and a little shifting of things around they still have the money, so I think there'll always - well at least for now I think they'll be there doing whatever it is that they do, creating the next Spice Girls or VH1 or MTV or Puff Daddy. All those things will continue to exist because it's been developed and the audience has been created for it. They've created an audience that needs that now.

JW: Tell me about the Arcana project.

BL : The concept was a vehicle that would involve Tony in playing music that wasn't jazz-based, that would be more related to what he did in the first two Lifetime records, where he was playing harder...I wouldn't say "rock music", but more aggressive drumming that involved moving a little bit out of the jazz form and putting him in an environment where there were more electric sounds or heavier bass & guitar sounds and more energy. And I

always wanted to do that for years and I always valued Tony as the most important drummer to me, the most innovative drummer who kept constantly evolving as a musician. So that was a priority to create this as a vehicle. We did some minor experimental thing and then when we did this record I thought this was moving more towards what the original idea was, and he never even got to hear the finished result of that - around the time I was finishing it, he died unexpectedly. So Tony Williams was always a priority for me, as a drummer for me he was THE drummer and will always be, and

there's a lot of great drummers now - Jack De Johnette is one, but Tony had a special thing that he did and there's no-one has ever played like that. The whole idea was to get into a situation - we had planned to make a group and to try to do live stuff and for him too to try to get out of people thinking that he just plays a certain style of drumming, which wasn't the case - he could play a lot of different things. He didn't make it to that, but I'm glad we did the one record.

BL : The concept was a vehicle that would involve Tony in playing music that wasn't jazz-based, that would be more related to what he did in the first two Lifetime records, where he was playing harder...I wouldn't say "rock music", but more aggressive drumming that involved moving a little bit out of the jazz form and putting him in an environment where there were more electric sounds or heavier bass & guitar sounds and more energy. And I

always wanted to do that for years and I always valued Tony as the most important drummer to me, the most innovative drummer who kept constantly evolving as a musician. So that was a priority to create this as a vehicle. We did some minor experimental thing and then when we did this record I thought this was moving more towards what the original idea was, and he never even got to hear the finished result of that - around the time I was finishing it, he died unexpectedly. So Tony Williams was always a priority for me, as a drummer for me he was THE drummer and will always be, and

there's a lot of great drummers now - Jack De Johnette is one, but Tony had a special thing that he did and there's no-one has ever played like that. The whole idea was to get into a situation - we had planned to make a group and to try to do live stuff and for him too to try to get out of people thinking that he just plays a certain style of drumming, which wasn't the case - he could play a lot of different things. He didn't make it to that, but I'm glad we did the one record.

JW: It's amazing, from start to finish.

BL: Yeah, I was really happy with it, we put a lot of time into it. And I think he approached it differently - we talked about trying to create extremes with different rhythm ideas from the drums.

JW: Did you use clicks (click tracks)?

BL: No.

JW: The timing is pretty amazing.

BL: Especially the cymbals - it almost sounds like film projectors running. But he had that ability - you can hear it especially on some of the earlier Miles stuff like right before "In A Silent Way" - like "Miles In The Sky", you can really see the development of the cymbal work coming. But he was to me the most innovative & important drummer ever.

JW: Tell me about how you got involved with the Master Musicians of Jajouka.

BL: I first heard Jajouka on the record that Brian Jones made there and I was immediately attracted to that. I don't know why - there was no explanation for why I should have been and it wasn't because it was Brian Jones - I wasn't particularly interested in the Rolling Stones at all (a little bit in Brian Jones because he seemed to be kind of open-minded in trying things), but it was just the sound of it which had a kind of terror in the tone of it and it was a very mysterious music. And then later on I realized that Ornette Coleman had gone there a few years later, and when I first came to New York, there were two records I was listening to - one was the Brian Jones record and one a record Ornette made called "Dancing In your Head", and at first I didn't realize it, but on one piece on "Dancing In Your Head" were the same musicians that he had recorded when he was in Jajouka. So when I met Ornette I started to talk to him about Jajouka - I was more interested in that than in any jazz history. Just what was it like going there and being there and doing that - it seemed impossible at the time like an incredible experience you couldn't imagine, actually doing it. It's like reading about Marco Polo or something. And he gave me videos of him there playing and I got a sense of what was happening.

I started to understand more about them from Brion Gysin and William Burroughs who had both been there, and I then found out it was Brion Gysin who took Brian Jones there, and it was through Paul Bowles that Brion Gysin learned about that music. So through their writing I started to get more and more of the whole mythic quality, that their concept of the Bou Jeloud is based on the Dionysis and the Rites of Pan loosely, that they have a Goat God who in a way has got the image of the Pan character. There's Aisha Kandisha who is supposed to represent a crazy woman who is his partner and there's all these different histories and stories of what goes on in the cave there and that once a year they have this ritual where the Bou Jeloud will appear and chase children, that he whips a woman with a branch and she immediately becomes pregnant and all these different stories. So I always wanted to do that. And then I heard that Bachir Attar, who was the son of Abdeslam Attar (who was the leader when Brian Jones & Ornette went), that he was living in New York. But I had heard not good things that he had done - nothing special, and then one day someone arranged a meeting, it was actually Vivian Goldman who set up the meeting, and a guy called David Silver, who was a filmmaker and who now works in a record company. And they all brought Bachir there to my house and he and his wife seemed very serious about making their thing known. And I said it's always been interesting to me, and I thought about it and I said, well I have a situation, we should do it, and within 3 months we were there.

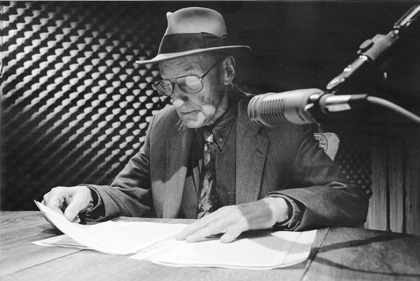

JW: How about William Burroughs - how did you start working with him, what do you think of him and what do you think was his contribution to the world?

BL: Well I always thought of Burroughs as not a book writer but a kind of philosopher in a way - a street philosopher. In that he did an amazing amount of research on things & he was especially fascinated with researching things that had to do with control and manipulating people. Like he did incredible research on CIA-influenced techniques and Scientology and L. Ron Hubbard and all kinds of things like that and he predicted early on a lot of things that affected people a great deal, like crack in urban communities or AIDS for example, and he foresaw a lot of things. And people always think of William Burroughs, the godfather of

Punk, the homosexual junkie who killed his wife, and I always thought that was nothing to do with the Burroughs I was interested in, the Burroughs who seemed to me incredibly humanitarian, and his works really seemed to me to be built on optimism and hope. So I was really incredibly influenced by him, but again not from his subversive writing. Because during the Punk days people saw him as sort of the godfather of that sensibility and except for getting a little money from it, I don't think he could care less about that, as he could care less about being involved in the Beats, really.

No-one needed to be called that - they just did it to sell a few books to pay the rent.

BL: Well I always thought of Burroughs as not a book writer but a kind of philosopher in a way - a street philosopher. In that he did an amazing amount of research on things & he was especially fascinated with researching things that had to do with control and manipulating people. Like he did incredible research on CIA-influenced techniques and Scientology and L. Ron Hubbard and all kinds of things like that and he predicted early on a lot of things that affected people a great deal, like crack in urban communities or AIDS for example, and he foresaw a lot of things. And people always think of William Burroughs, the godfather of

Punk, the homosexual junkie who killed his wife, and I always thought that was nothing to do with the Burroughs I was interested in, the Burroughs who seemed to me incredibly humanitarian, and his works really seemed to me to be built on optimism and hope. So I was really incredibly influenced by him, but again not from his subversive writing. Because during the Punk days people saw him as sort of the godfather of that sensibility and except for getting a little money from it, I don't think he could care less about that, as he could care less about being involved in the Beats, really.

No-one needed to be called that - they just did it to sell a few books to pay the rent.

JW: What do you feel is the ideal state of mind for a producer or maker of music? Innocence?

BL: By opening up, just giving in to that and being free from a lot of things, you come into contact with something that can help you, that will give you these results. In other words, in a way, it's kind of saying that ignorance is very much a part of that. Because I'm not trying to know something or teach something or learn something & be about something, I'm trying to just get rid of everything and feel something and let it happen. I'm not saying be stupid, I'm saying get away from the brain. Children don't have that problem, nothing is between them and what they want or what they're interested in because it hasn't been put into their head - they're not completely covered with fingerprints.

A lot of people who do popular music are concentrating on creating whatever they did last time that worked. This idea of creativity or doing something innovative or involving is the enemy of a complacent approach to success. Because all these things are not going to lead anyone to a major financial success - these things are the enemies of commerce and corporations and successful artists in a way